Islamic Finance - Fad or the Future? - Part 2

Part two of an analysis of the implementation of Islamic finance in the Western business culture and its compatibility with changing economic trends.

Before reading this article, make sure you read part 1:

Introduction

In our previous article, we looked at Islamic Finance and how it worked within governments around the world and how durable it was under stressful conditions like the GFC. The general consensus is that under Islamic finance, growth is relatively stunted. It limits the kind of products that can be offered and assesses each based on their risk appetite. In summary, growth was not as explosive as debt finance-addicted countries but also suffered much less when those credit markets imploded. Today we’re covering real-life examples of where these principles of finance have been implemented and how they can be used to tackle issues plaguing the world today, like Inflation.

Economic viability

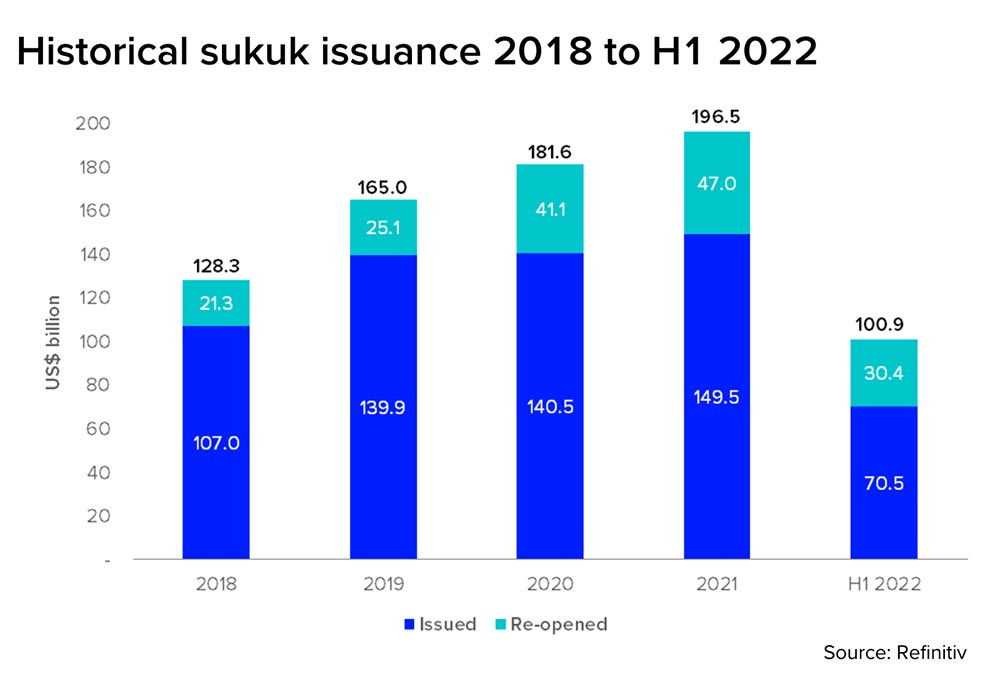

As Islamic finance exists in a world with diverse economic outlooks, it is also vital to evaluate whether its’ products are fundamentally incompatible with the Western business culture[1]. Sukuk investments are perhaps the most contemporary examples of Islamic credit products used in the West. A Sukuk is a financial certificate that is like a Shariah-compliant bond. As the traditional Western interest-paying bond structure is not permissible, the Sukuk issuer sells an investor group a certificate, using the proceeds to purchase an asset that the investor group confers partial ownership interest [2]. This bond grounded in equity seemed to be an ideal intersection between the two different financial systems when the Islamic Development Bank in 2003 issued the first Islamic bond backed by a pool of assets named the five-year, fixed-rate $400 million Eurobond[3].

The Islamic Finance Development Report (IFDR) categorized Sukuk as the second largest sector of the global Islamic finance industry, accounting for $426 billion of the industry’s total value of $2.4 trillion[4]. However, in 2017, UAE-based commodities firm Dana Gas announced that a $700 million Sukuk it held was incompatible with Shariah, thus putting the entire portfolio held by Investors in Western nations at risk. This outlines the fundamental issue of incompatibility with Western finance on the core issue of religious approval. Integration of religious oversight and financial markets is antagonistic in some nations but acceptable in others[5]. Although the Dana Gas case had been settled out of court and the shariah compliance issue left untested in the UAE, it introduces substantial uncertainty to foreign investors’ risk matrix where they must submit their investment to a secondary layer of scrutiny by Islamic regulatory bodies and courts.

Regardless of potential gains yielded from Islamic finance, the additional risk poses a significant inconvenience. At face value, these instruments adopted by banks have attempted to minimize riba but do little to supplement the products with the security and general stability that debt obligations bring.

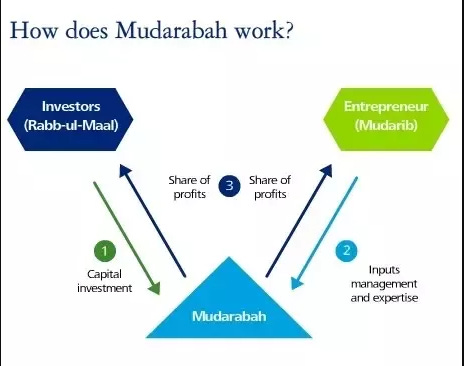

Another example is the Profit and Loss Sharing system (PLS) adopted by Islamic Bankers. PLS is a system of finance used by Shariah-compliant institutions to comply with the restriction on interest. There are two main forms of profit and loss sharing used by Islamic banks called Mudarabah: passive partnership contracts and Musharakah, which confers ownership through equity participation contracts[6]. These contracts vest institutions with equity stakes in businesses in lieu of Interest premiums. A complete conformation to PLS would pose great risks to economies, requiring banks to take direct equity stakes in every investment.

You’ll notice that equity is the preferred way of trade over debt in Islamic Finance. It is a common notion that the issuer should share in the responsibility and the fruits of the person next to him.

As such, it is evident that the equity-based system of finance in Islamic law is effective in hindering toxic credit products; however, the PLS system requires banks to assume more risk, therefore leaving them heavily exposed to economic downturns where a substantial loss in the financial sector then also shared amongst smaller businesses who are unlikely to have factored such fluxes in stability[7]. It is evident that there are apparent flaws in Islamic finance laws where the instruments used do not address the core issue of minimizing risk to financial systems and merely appeal to religious consumers by replacing debt obligations with equally risky obligations in equity.

Compatibility with changing economic trends

As the financial system is an essential component of how an economy functions, it must be stable & resilient enough to weather and be able to adjust to shifting macroeconomic trends both domestically and globally. As such, there appears to be an apparent disconnect between the ability of insular Islamic Banking systems to ingest foreign market changes. The conventional banking model allows for derivative and debt instruments such as Futures, forwards & swaps, which are used for hedging risk. Hedging uses debt instruments to protect the downside of financial risk and reduce a company’s exposure.

Interest rate swaps, and similar plain-vanilla derivative products, are an effective and transparent mechanism to separate the interest rate risk.

Prohibiting Riba instruments leaves institutions' asset-backed capital largely unprotected[8]. Essentially the liability to use debt contracts to hedge out exposure leaves Islamic banks largely defenseless in stabilizing the value of the real assets in their portfolios. A lack of free-flowing paper would contract credit facilities, and State central banks are left incapable of stimulating economies by buying bonds & commercial papers to offset a liquidity crisis[9]. The inability to freely move funds in the event of bank insolvency issues limits the viability of Islamic Finance to deal with a large institution or economy’s risk exposure[10].

Islamic Contract Law

Gharar is an Arabic word that is associated with uncertainty, deception, and risk. It has been described as "the sale of what is not yet present," such as crops not yet harvested or fish not yet netted. A key component of this is Islamic contract law, such as Gharar, which weighs in favor of contract integrity but comes at a higher cost. Islamic finance Is dearer as it often requires more than one contract to ensure fairness and limit the maneuverability of parties to breach them. Islamic Institutions attempt to create conventional banking products that varied in accordance with Shariah. Various products will require additional administrative and legal fees, such as hire purchase agreements, multiple sales, special-purpose vehicles, and documentation of title. Islamic credit cards also require banks to immediately buy and sell the good to the customer at a significantly higher cost[11].

In summary, although much more costly and with higher premiums, Islamic contract law focuses on simplicity in contracts where the main questions to ask are, has the asset been provided, and has it been squarely paid for? Although complex contracts cannot be avoided, applying this to even smaller situations for average people who want to buy a stock, or a gym membership, or want to take part in an IPO, the principle stands that you should Keep It Simple, Stupid (KISS). The less complexity, the less leeway a party has to abuse the counter-party.

Conclusion

We’ve gone over quite a bit in the last two articles. It was a journey, but it was worth it. In summary, Islamic law seeks simplicity, not out of an inability to absorb complex contracts but out of necessity. Complexity, speculation, and risk are all things that are out of your hands. Call it God. Call it the free market. Our article on Crypto gambling will show you how unregulated risk and speculation can bankrupt and destroy societies. Even if Islamic finance grows slower, is that so bad when you know that you will be paying quintuple the amount with a conventional loan? We must grow beyond the thinking of unsustainable and persistent growth. We need sturdier banking principles that protect all parties, not just the one with all the money. If you doubt this, ask yourself when was the last time you signed any financial contract without feeling that something wasn’t right. Question everything and stay safe.

We sincerely hoped you enjoyed this series. This one took a lot of effort to put together, and we will be switching to more relaxed articles but will be back with more like this soon.

🗡️Thank you for reading our work and supporting our message🗡️

References

[1] Black. A & Sadiq. K, Good and Bad Sharia: Australia’s Mixed Response to Islamic Law, (2011), UNSW Law Journal, Vol. 34

[2] Huma. N, S. Bukhari, & Ali. S, Compliance of Investment Sukuk with Shariah (2014), Science international-Lahore.

[3] Domonic Dudley, Middle East: Has Islamic banking set a new standard? Euromoney, (March 5 2019)https://www.euromoney.com/article/b1dbwnl8vg0wrv/middle-east-has-islamic-banking-set-a-new-standard (Date accessed, 20/10/20)

[4] Islamic Finance Development Report, (2018), (accessed 20/10/20) https://ceif.iba.edu.pk/pdf/Reuters-Islamic-finance-development-report2018.pdf

[5] Dana Gas PJSC v Dana Gas Sukuk Ltd & Ors [2017] EWHC 2928

[6] Khan. F, Islamic Banking in Pakistan: Shariah-Compliant Finance and the Quest to make Pakistan more Islamic, (2015), Pg.91

[7] ibid

[8] Irfan. H, Heaven's Bankers, (2015), p.163-4

[9] Khan. F, Islamic Banking in Pakistan: Shariah-Compliant Finance and the Quest to make Pakistan more Islamic, (2015), Pg.91

[10] Ali. S, State of Liquidity Management in Islamic Financial Institutions, (2013), Islamic Economic Studies

[11] Rogak. L, Shariah-compliant credit cards become more common (2008).

[12] ibid

This was a tough one to grasp but I appreciate the effort went by the writer to simplify.

Without question the inequality in western finance is largely brought about by making things too complex for the layperson to grasp, leaving it to be an exclusive club for those with the means to educate themselves on it